Synopsis

Ivy League schools are comprised of high achieving students that can be three times more anxious and depressed than the average pupil. They overburden themselves to get into top schools only to spiral once they get there. When students seek campus therapy, they often learn that their well resourced institutions lack sufficient mental healthcare infrastructure. People living with mental disabilities remain largely underserved. The academic and social design of Ivy Leagues perpetuates stress culture that aggravates underlying mental illnesses. Mental illness is a risk factor for suicide. When schools fail to provide effective mental health support, students die.

This story is about those whose mental illnesses have shaped their struggle at the Ivy League; whose greatest challenge is surviving.

surviving ivy on instagram

The latest stories about mental health discrimination in higher education.

trigger warning

This story contains references to self harm.

Angie Wallace

Leaving her son Taylor at Columbia University made Angie Wallace nervous. But that’s almost every parent on college move-in day. She knew her child was intelligent. He would do well at Columbia. Leaving Brookfield, Missouri, a town of just over 4,000 people, to live in a city of eight million wasn’t daunting either. She thought he’d be happy around driven, talented kids like himself. Making friends would be easy for someone as kind and loving as Taylor. What she didn’t know, she asked the head of Columbia’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CPS).

Wallace was concerned about Taylor’s mental health. He took Lexapro, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), to treat his depression. The head of CPS reassured Wallace, stating that many Columbia students took antidepressants. She scribbled her direct number on a card and asked Wallace to give it to Taylor. So she did.

Wallace wished he used the number. Taylor was miserable. He told her so every night from the isolation of his 90sq ft room on floor 14 of John Jay Residence Hall.

“He would FaceTime me at night and say, ‘You don't know how bad I want to jump out this window right now,’ said Wallace. “And I said, Taylor, don't say that. He's like, ‘I know, but I just don't like it. I don't want to be here.’”

It wasn’t the first time Taylor casually mentioned suicide. He shared everything with his mother. Because he talked about it, she never thought he would actually do it. The thought of returning home for Homecoming kept Taylor motivated. He fell into a dull, monotonous, routine: class then Netflix. When Taylor finally returned to Brookfield, he had a revelation. The school he’d dreamt about since age nine was not a good fit. He wanted to withdraw.

Concerned for the wellbeing of her child, Wallace called Taylor’s academic advisor. His advisor agreed that Columbia was simply not the right place for everyone. She told Wallace that if she were Taylor’s mother, she would let him come home. On October 1, 2016, Taylor moved back to Missouri.

“He gave me the biggest hug,” said Wallace, “I felt every ounce of his soul when he gave me that hug. He was just so relieved to be back.”

After getting some rest, Taylor began working at a local hospital. He was planning to start school January. Just like that, Taylor was back to pursuing his dreams of becoming a cardiothoratic surgeon. He was going to save lives.

On October 27, 2016, Wallace took her family to Truman State University. Taylor talked to the baseball coach about joining the school’s team. He also charmed Truman State’s Director of Admissions. Wallace said Taylor had his heart set on attending Truman State. He was on “cloud nine.”

Then, Taylor was overcome by a wave of depression. He lost his appetite, slept a lot, and became very withdrawn. When Taylor told his mother he was skipping dinner, Wallace thought nothing of it. Taylor took his life in the basement. His dad found him. Immediately Angie and her family sprung into action. Taylor’s 15-year-old brother administered CPR. At first, it worked. Taylor was temporarily revived, but he later passed away in the hospital.

Wallace worked through her loss by starting The Taylor Gilpin Wallace Foundation for Suicide Prevention. She has since created Moms Breaking The Silence alongside other Brookfield mothers who have lost their boys to suicide. Taylor’s father still goes to grief counseling. Wallace’s youngest son went to therapy after a series of nightmares. He is now a student at the University of Missouri.

Suicide is a public health problem.

Suicide is a public health problem. It is the second leading cause of death in late teens and young adults in the United States – and it’s getting worse. Like many high achieving students, Taylor had underlying mental illnesses. At 18-years-old, he was not used to overcoming adversity. Wallace said her son was so young he hadn’t developed “healthy coping mechanisms.” His story is tragic, but it’s many students’ stories. There is never a sole motivator in a students’ decision to take their life. Mental illness, relationship issues, and prolonged stress can influence suicidal ideation. The American College Health Association estimates that more than 10% of undergraduates contemplate suicide. College is a stressful coming-of-age experience for most young adults. It’s the first time people have to cope with life’s challenges away from home. This is especially true for individuals like Taylor who attend an Ivy League institution. High school overachievers who’ve spent their entire lives being exceptional feel average at elite schools, and not in a good way. Ask any Ivy League grad and they’ll probably remember at least one instance of suicide that occurred during their academic career. This is what happens when schools have lethal stress cultures and insufficient mental healthcare.

As leaders in higher education, Ivy League schools like Columbia set the standard for suicide prevention. This often entails providing accessible mental health treatment, minimizing environmental risk factors, and raising awareness. Yet, Columbia and Barnard were generally uncooperative to questions regarding suicide prevention and campus statistics. Death is bad for business. Harvard’s Director of Health Services has yet to present the findings of a 2018 campus-wide survey about mental health. While these schools have attempted to remedy the problem, they remain painstakingly vague about their efforts to save lives. Although Ivy League officials insist that their campus suicide rates aren’t any worse than other schools, they certainly aren’t any better.

Painstakingly Intransparent

It is impossible to account for every student death when private colleges keep their statistics under lock and key. This makes understanding the frequency of student suicide fairly difficult. While it’s is not a Columbia specific problem, I focused on tracking Columbia student deaths because it’s my alma mater. I got death notification emails nearly every semester that I attended Barnard. So I compiled all of the emails and cross referenced them with articles from various news publications. Since Barnard and Columbia refused to release statistics, I tracked their histories of student suicide from 1902 to 2019.

Since 2016, at least ten additional Columbia students have committed suicide.

Six Cornell students killed themselves in 2010, and at least four additional students died after that. The nets under the Cornell’s idyllic bridges serve as a physical reminder of its history. Not to mention that Cornell’s longtime Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) lead killed himself after starting a job at the University of Pennsylvania. The Daily Pennsylvanian reports that at least 14 University of Pennsylvania students have taken their lives since 2013. Harvard, Dartmouth, Yale, Brown, and Princeton do not release suicide statistics. Their deaths are harder to track because they did not receive as much media coverage.

Some people flourish at Ivy League schools. Students with healthy home lives have social support. Boarding school alums tend to handle the transition to college relatively well. They are used to managing a sizable workload while living away from home. White Ivy League students do not deal with microaggressions, blatant racism, or imposter syndrome like Black and brown students. People who are cisgender and heterosexual aren’t marginalized for their gender identity or sexual orientation on campus. Neurotypical people also tend to have smoother experiences at school.

Ivy League schools are comprised of high achieving students that can be three times more anxious and depressed than the average pupil. This can result in elevated rates of substance abuse and delinquent behaviors. The academic and social design of Ivy Leagues creates a stress culture that aggravates underlying mental illnesses. Mental illness is a risk factor for suicide. When schools fail to provide effective mental health support, students die.

Every school has tried to improve its mental health resources but many students continue to suffer in silence. Harvard, Yale, Brown, Princeton, Cornell, and the University of Pennsylvania have all been sued for wrongful death, negligence, or discrimination against mentally ill students. The courts are currently reevaluating laws regarding university culpability for student suicide. Failing to accommodate disabled and mentally ill people does not preserve the academic integrity of the Ivy League. It’s discrimination. This story is about those whose mental illnesses have shaped their struggle at the Ivy League; whose greatest challenge is surviving.

Count of Deaths Across Schools (Estimate)

Deaths By Class Year Since 2016 (Estimate)

Deadliest Months Since 2016 (Estimate)

In accordance with nationwide trends, Columbia’s suicides have increased. The average victim’s age has decreased.

What is stress culture?

Not many people have been an undergraduate student at two Ivy League schools — but Liam Riley was. By February of his freshman year at Columbia, he had completed several transfer applications. He found Columbia’s general education requirements, the Core Curriculum, particularly “annoying.” When he wasn’t working, he was with his sick grandmother. Visiting her three times a week while balancing Columbia’s Core was tough. The situation left Riley feeling incredibly unsupported by his school. Now, he’s a Yale grad. Riley believes transferring was worthwhile, but not in terms of the stress.

“I think people were working a lot more at Columbia and more sleep deprived,” said Riley. “I don't think that mental health was any better at Yale.”

Riley says paying Yale’s student contribution is stressful for many people. He had to work a few jobs to pay off his $2,500 bill with his mother’s help. He explained that first generation students enroll thinking full financial aid means they won’t have to work. Then they struggle to juggle school, extra curriculars, and several jobs. At Columbia, Riley saw the Core as a major source of stress for first years.

“People were worked hard at Columbia from the jump,” said Riley.

Core classes constitute nearly 44% of the total credits for Columbia College students. The Technical Core comprises 41% of engineering students’ courses. Most of these classes cannot count towards any major. Therefore, the structure of the Core thrusts students into “demanding,” classes as soon as they arrive on campus. Riley took 16 credits during his first semester at Columbia. He says Yale students are encouraged to take no more than 12 credits. This allows for little to no build up in rigor, which makes adjusting to the workload difficult.

Riley noted that conditions are worse for engineering students. The stakes are higher for an engineering student who doesn’t complete a problem set than they are for a humanities major who didn’t do all the readings. Riley believes engineering professors at Columbia and Yale were the least compassionate of all.

“It just seemed like so many of their professors didn't care or had a blatant disregard for rules around workload,” said Riley. “The projects that they would have to do, they'd be in their engineering labs super late.”

Technical Core classes are notoriously hard, and Columbia Core classes are credit heavy. Columbia administrators knew students were taking overwhelming course loads. In 2017, they reduced the credit maximum for Columbia College students from 22 to 18. The Core was not restructured. Columbia's goal was to “reduce excessive academic pressure,” by expecting students to complete the same courses with less opportunities to do so.

The Core Curriculum is designed to create a shared campus identity. But according to Riley, it looks like “800” first years studying for the same exams simultaneously. Campus stress culture is highly visible, and it smells.

“You walk into Butler Library and you see people studying in desks like all day and night,” said Noah Stubblefield, an engineering student at Columbia.

Almost every Ivy League school has a 24 hour study space. At Columbia, students forgo sleep and personal hygiene to study for days in Butler, Columbia’s 24 hour library. The smell of body odor emanating from the building is a reminder that productivity is more important than self care on Columbia’s campus.

Despite Columbia Health’s emphasis on rest, Columbia Campus Services opened a 24 hour cafeteria. JJs Place is a popular campus dining hall located in the basement of a freshman dorm. Its hours were extended to offer communal space, but what kind of stress necessitates a 24 hour dining hall? When are students supposed to sleep? In 2014, Columbia students were the most sleep deprived in America. Barnard still sells magnets promoting all-nighters in its campus store.

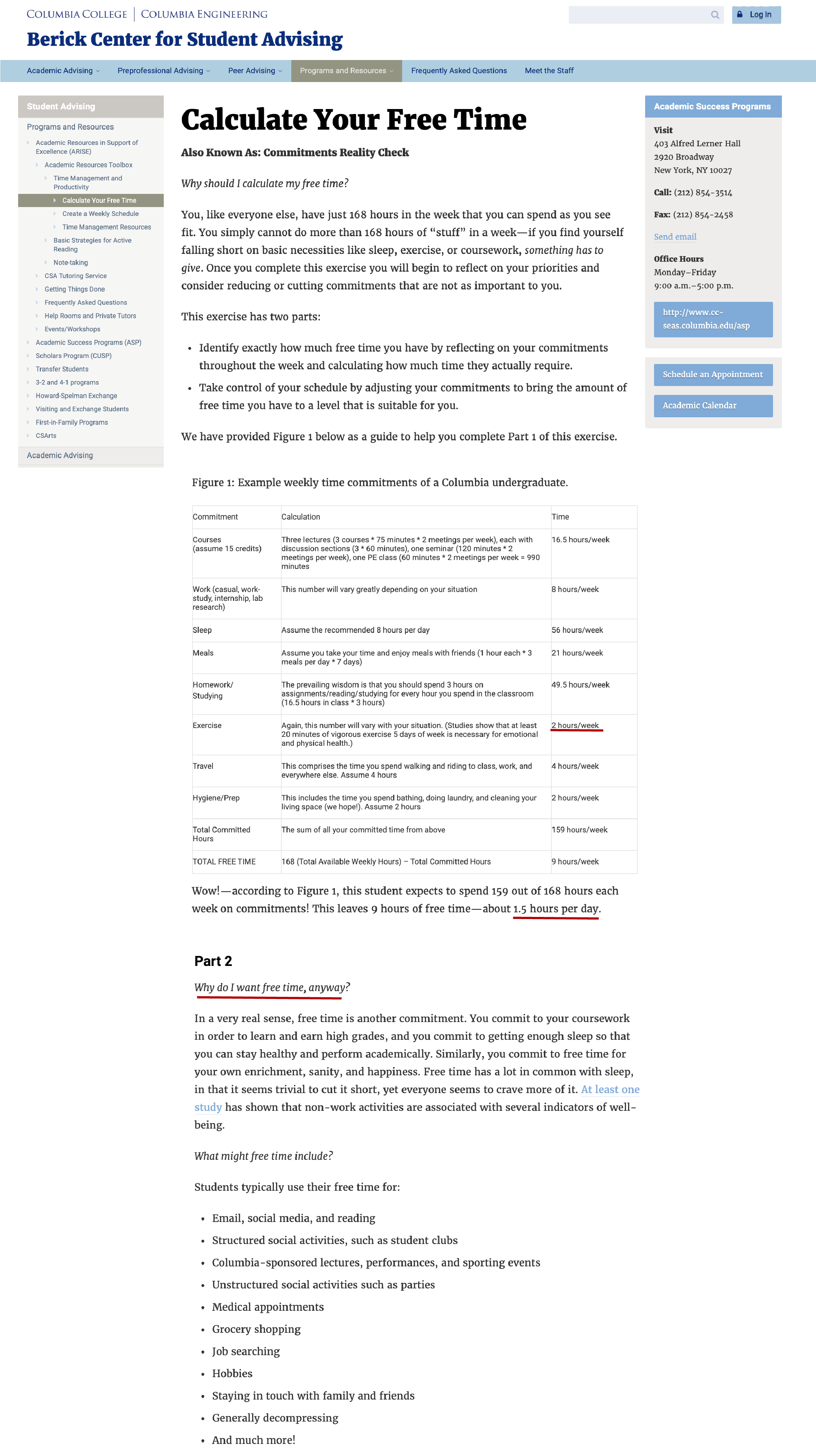

To help students budget their time, Columbia’s Center for Student Advising published a “Free Time Calculator.” Students hated it for a host of reasons. Columbia’s “calculator” only allows for an hour and a half of free time per day. Students said it wasn’t enough time to see a doctor in Urgent Care or go to therapy. Dining hall overcrowding makes it almost impossible to eat in under an hour. The chart completely ignored student athletes. People were outraged that Columbia only set aside two hours per week for showers, laundry, and personal upkeep. Its declaration that “free time is another time commitment,” epitomizes Columbia’s stress culture.

Columbia’s Free Time Calculator

“Free time is another time commitment.”

Students at top colleges enjoy learning. They study because they want to do well in school. Like anything, studying is safe when done in moderation. Alas, high achieving students at top tier schools tend to take studying to dangerous extremes. When students say “stress culture,” they’re referencing environments that normalize, praise, or require self-destructive study habits. Such behaviors prioritize productivity above all physical needs like sleep, meals, and proper hygiene. It also incentivizes stimulant and study drug abuse. All of these behaviors adversely affect a students’ mental health. Studies indicate that venting about stress can be healthy but stress culture treats it like an olympic sport. In these environments, suffering is intrinsic to the identity of a “good” student. University of Pennsylvania undergraduates coined the term, “Penn Face” to describe seemingly perfect students who are really struggling in silence. People intentionally overburden themselves because having a manageable schedule is cause for shame.

Stress culture emphasizes toxic study habits, not for the sake of learning, but for some level of social validation. I asked students across Ivies to describe stress culture in their own words.

Do grading policies contribute to student stress?

Meme about grade inflation at Harvard.

Three years ago, rumors about lax grading standards at Harvard were validated when a dean announced that the median grade at Harvard College was an A-, and the most frequently awarded grade was an A. Professor Harvey Mansfield said if the dean’s statement was true, it constituted a “failure to maintain academic standards,” on behalf of Harvard’s administration. Students often say, “the hardest part about Harvard is getting in.” Christian Porter, Harvard ‘23, says that’s not the whole story.

“STEM here is hard. Harvard inflates grades, but not in the way that people think, not everyone is going to get an A,” said Porter. “Even if you are failing the midterms, you'll probably end up with a C.”

Supporters of the policy argue that grade inflation and deflation are more related to competition than academic rigor. Grade deflation at Princeton is often cited as an example of this. For nearly ten years, Princeton’s grading policy suggested that no more than 35% of students receive A’s. Eventually Princeton’s president recognized that its former grading policy was a “considerable source of stress for many students.” The stress he was referencing could be a product of “manipulative” behaviors used by high achieving students to game the grade deflation system, as explained in the Atlantic in 2013. Cut-throat student competition inspired by grading policies perpetuates stress culture.

Princeton phased out its campus wide grading mandate in 2014, but decentralization may preserve grade deflation in some departments. A 2019 study by RippleMatch reported that Princeton has the lowest average GPA in the Ivy League. Justin Hinson, Princeton ‘21, thought grade deflation made students extra tough on themselves.

“When most kids talked about how they did [on exams], they were so disappointed to see A-’s, B+’s, and B’s, said Hinson. “It just didn’t make sense to me why other students would stress so hard about the little things.”

Grades do not reflect anyone’s inherent worth. But for people who’ve spent their entire lives being the best, it can feel like it.

When do students internalize elitist ideas? How can those ideas induce stress?

Cornell has the second lowest Ivy League campus GPA, but it isn’t considered to be as prestigious as Princeton. Instead students say it’s the “easiest Ivy to get into but the hardest to get out of.” This euphemism backhandedly validates Cornell’s Ivy League status despite its “high” acceptance rate, by acknowledging its level of difficulty.

Meme about Cornell stereotypes.

Marcus Trenfield, Harvard ‘21, learned about elitist hierarchies while he was a student at Lawrenceville, a prestigious boarding school. As a child of Black and Latinx immigrants, his family expected a lot of him. Trenfield’s parents believed they’d be in a better place if their elders had prioritized education. So, they went the extra mile to impress the importance of scholarship to their son. Alas, they didn’t know much about college. Their main point of reference was Princeton because it was a 15 minute drive from home. When Trenfield got a B in middle school, his father told him he needed to get straight A’s from that point on. Trenfield says it freaked him out. His parents’ message was clear: “you cannot afford to fail.”

“It was like ‘Marcus, you are supposed to go to a good school because you are not only supposed to support yourself, but you’re supposed to support your sister, and us, and your extended family,” said Trenfield.

Attending one of the world’s most prestigious boarding schools brought Trenfield one step closer to achieving his Ivy League dreams. Every student was expected to excel in academics, sports, and extra curriculars. Nearly a quarter of Lawrenceville graduates matriculate into Ivy League schools. Trenfield knew rich kids went to Lawrenceville, but nothing could’ve prepared him to witness gross displays of wealth. One of his peers needed a U-Haul to move into their tiny dormitory.

“They put flat screens in every single room,” said Trenfield. “And they put carpet on top of carpet because they didn’t like the way our carpet looked.”

He was learning alongside the children of billionaires. Trenfield wasn’t well off, but he saw how pressure to succeed transcended class. One girl’s mother spent half a million dollars on an Ivy Coach to model her entire life so she could get into the Ivy League. She planned to spend another $500,000 after her daughter was admitted.

“They are using their kids as a status symbol,” said Trenfield, “I feel so bad for that girl whose mother invested that much money, because that pressure would destroy me. To think, if I don’t get into an Ivy, I’ve lost them a million dollars.”

The vast majority of Lawrenceville students were raised by college graduates. Trenfield was not. He knew he was supposed to go to an Ivy but knew nothing beyond that. His peers were knowledgeable about the standing of elite schools from day one.

“You see seniors get into colleges, then you hear people talk about the seniors in certain ways,” said Trenfield.”Then you’re like ‘Okay, so that’s how this college is viewed.’ And it keeps perpetuating itself.”

They viewed the most selective schools such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale as top-tier Ivies. When an Ivy League school wasn’t exclusive enough to be considered top-tier, they were evaluated by the perceived intensity of their institution. For example, the pace of Dartmouth’s quarter system makes it extremely hard and, therefore, extremely valued. Likewise, they respect Columbia’s extensive Core Curriculum.

Elitist hierarchies and stress culture at Cornell, NYU, and Columbia.

An average acceptance rate of 6.7% hints that Ivy League prestige is predicated on exclusivity. Therefore, Cornell’s 10.6% acceptance rate seems high. Trenfield admitted that his classmates didn’t hold Cornell in high regard compared to other Ivies. At Lawrenceville, a student’s social standing was determined by college acceptances.

“People would base who you were on your college admissions,” said Trenfield. “Students who were passionate high achievers would lose their status because they didn’t get into an Ivy League.”

Trenfield says he flew under the radar until he was admitted to Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Dartmouth, and Brown. Then came the hate.

“People would get really depressed about Ivy Leagues,” he said. “They'd get really mad at other students.”

His Harvard acceptance euphoria faded after classes began. Trenfield was disconnected from his Lawrenceville friends, fresh out of a relationship, and far from home. At first he had a hard time finding community. He went from being a big fish in a small pond to a normal fish in a big pond. Despite his academic and extracurricular achievements, Trenfield wasn’t happy.

“I was like ‘It’s not all going well, that means I’m not doing well enough at Harvard,’” he said.

Trenfield went to therapy at Lawrenceville but stopped after his parents ridiculed him for it. This made him hesitate to visit Harvard’s Counseling and Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Upon learning that CAMHS visits were confidential, Trenfield used their services.

A gastroparesis diagnosis changed his outlook on life. Suddenly he was too ill to attend class or eat solid food. He lost 30 pounds. He had to take a medical leave. Six months later he returned with a new perspective. Being the best was “unimportant.” He now works with Harvard’s Student Mental Health Liaisons.

Trenfield said that his unhappiness at Harvard was a culmination of feelings he’d repressed for years. As a Black first generation college student, his parents expected him to uplift his entire family. At 13-years-old, they prepared Trenfield to follow a formulaic model for success. Like many working class families, Trenfield’s parents pushed him into stressful elite environments to achieve upward social mobility. Trenfield pursued medicine because it guaranteed a future his parents deemed respectable. For a long time, it diminished Trenfield’s confidence in his ability to chart his own path. When high achieving students stumble on a predetermined path to success, their worlds can fall apart. Especially when they feel like their parents' support is conditional upon their success.

Building identity within a culture predicated on exceptionalism may result in tragedy.

Are leaves discriminatory?

Exhausted and distressed, B. Hernández hoisted the last of their possessions up a fifth and final flight of stairs. It was January 11, 2020. A few days ago, Hernández was preparing to begin their last semester at Columbia. Now, they were splitting a room with their 16-year-old sister in their modest family apartment. Hernández had no privacy and even less space to breathe. Finally, they could accept that Columbia had chewed them up and spit them out.

Hernández’ name was omitted because they feared retaliation from Columbia.

Born and bred just five stops away from Columbia, Hernández dreamt of being a pediatrician. After they were sexually assaulted, they began seeing a campus therapist weekly. During their junior spring, Hernández’ was told they’d have to leave campus for counseling. It was inconvenient, given their demanding academic schedule. To remedy the situation, their therapist suggested Hernández take a voluntary medical leave. Hernández took their counselor’s advice. They said the leave was necessary, but it wasn’t very restful. Hernández felt guilty for not being in school. When they returned to Columbia in fall 2018, things seemed okay.

A year later, they were on academic probation. Mentally, they were spiraling. Hernández lost ten pounds in two months. They weren’t hungry. Hernández either slept all day or didn’t sleep at all. Small tasks like emailing seemed onerous. At some point they couldn’t tell when things began or ended.

“I hit a huge depressive episode,” said Hernández, “It didn't help that someone got killed on campus.”

In December 2019, a Barnard freshman named Tessa Majors was murdered near campus. News of her death sparked widespread campus grief. Hernández didn’t know Majors but her passing hit home. Hernández assumed assignment extensions were reserved for those who knew Majors. Their debilitating depression was compounded by campus grief. Final exams were a nightmare and it showed in their grades.

On January 7, 2020 Hernández received an email from their academic advisor. The advisor said Hernández’ recent academic performance was grounds for dismissal from Columbia. Their only chance to save their academic career would expire in less than 24 hours. Hernández had to write a letter begging the Committee on Academic Standing (CAS) to let them stay.

Anxious and scared, Hernández submitted the letter. The Committee responded in under three hours. They suspended Hernández for a year during their senior spring. In accordance with Columbia’s academic suspension policy, Hernández was required to take six to nine credits at another four year college. Failing to do so would result in expulsion. Hernández was a part of the Higher Education Opportunity Program (HEOP), which supports students whose families cannot afford tuition. Requiring a HEOP student like Hernández to take classes without offering financial aid was like asking them to fly with no wings. Even though Columbia agreed to let Hernández take three to six credits, it was still financially out of reach.

“The whole reason I came to Columbia was so I wouldn’t have to take out loans,” said Hernández. “They gave me the most money. Now, I have to take out a $3,000 loan to just take a class at City College?”

Through tears, they asked their advisor how to pay for it all. The advisor didn’t have an answer. So, Hernández requested a medical leave. They were angry. At first, they blamed themselves for being too depressed to do well in school. Over time Hernández came to resent the University’s handling of the situation. Hernández wished they were more involved in the Committee’s decision making process.

“You made this decision in a few hours,” they said. “Why wasn’t I in that room? I should’ve been in that room to represent myself and to explain myself.”

Hernández hated being too poor to adhere to the guidelines of their academic suspension. Their life had been turned upside down in only four days. They had 48 hours to vacate their spacious Riverside Drive dorm. Moving on short notice was expensive, even though they lived in Washington Heights. To afford the move, Hernández sold some of their belongings. Their home life wasn’t the worst, but adjustment would take time. Either way, they’d have to make it work — at least for the next year.

Hernández’ situation highlights several issues with leave of absence policies. There were few opportunities to self-advocate. The timeline they were given to do so was unreasonable. As such, they couldn’t fully explain how depression affected their grades. The execution of their leave induced stress and anxiety. They couldn’t afford the provisions of academic leave. At no point were they asked whether home was safe.

LeavE CAN be restorative.

When schools hastily remove students from campus, they can land in potentially dangerous situations. Cornell almost sent a transgender student back to an unsafe, transphobic household. Fortunately the student was able to find lodging elsewhere on short notice. Quickly evicting students can make it harder for them to heal and seek care. This is counterintuitive, as schools often require students to be medically cleared before re-enrolling. It can be particularly difficult for people who are queer.

“Maybe you're in a small town where like finding a therapist that’s supportive of LGBT people is impossible,” said a Cornell student. “It's a vicious cycle.”

Sometimes, staying on campus during leaves is best. When asked whether Harvard would knowingly send a student back to a toxic home, an administrator couldn’t say no. Harvard does not plan to offer alternative housing options for students on leave. The administrator reiterated that Harvard exists to disseminate knowledge. Harvard’s faculty may not support a “social service” like providing campus housing for non enrolled students.

Stanford disagrees. As of January 2020, Stanford students can petition to “retain campus housing when on leave for a term.” Disability lawyer Monica Porter says the policy protects students from being forced to return to “unsafe or un-therapeutic” living situations. The new changes were the product of a class action lawsuit filed against the university. When Stanford students sought mental health support, they were coerced into taking “voluntary” leaves. If they didn’t seek support, they were punished. Stanford’s new approach is hailed for being “student-centered, compassionate, detailed, and transparent.”

Miriam Heyman is a fan of the policy. She published a study on “leaves of absence for students who are experiencing mental illness.” It said Ivies’ leave policies were “ambiguous at best and discriminatory at worst.” Princeton and Yale have been sued for discriminatory leave. A Dartmouth student said his leave felt like a punishment for being depressed. Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, and Yale ban students from campus during leave. A Columbia administrator defended the school’s policy. They argued that removing students from campus invites them to build an identity separate from school. Columbia is aware that students violate this rule, but it’s not enforced.

Heyman said that severing students’ social support mechanisms can make it harder for them to heal. Several Columbia students have committed suicide while on leave. Liam Riley, Yale ‘19, suspects the same thing is happening at Yale. It’s hard to tell when schools don’t always report deaths that occur during leave.

Columbia administrators also insist that involuntary leaves are extremely rare. Heyman said that schools may be pressuring students to take “voluntary,” leaves. A former Columbia student was cajoled into a “voluntary” leave. She had suffered a mental breakdown and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Columbia sent her home to live with a parent struggling with substance abuse. However, the school paid for her medical insurance. When she got better she reapplied to Columbia in June. She was rejected two weeks later. She said the situation made her feel like a liability.

Buzzfeed reported a similar story about a Brown University student who received a cease and desist letter during his leave. He was put on leave following a suicide attempt. Even though he sought therapy and excelled as a visiting student, Brown refused to let him reenroll. They rejected his readmission application five times.

Forcing people to leave campus doesn’t exactly encourage them to seek help. A Dartmouth student who was suicidal said he’d never tell his school.

“They’re going to medically withdraw me,” he said. “They only ask you [if you’re suicidal] because then you become a liability issue.”

By forcing mentally ill students to take leaves, colleges send a simple message: If you’re going to kill yourself, just don’t do it on campus.

What is the state of campus care, and is it sufficient?

When students are on campus, they use counseling resources. Triage, a brief consultation, is often students' first step towards care. Then, they wait to be paired with a counselor. The amount of time between triage and seeing a therapist varies. So does the length of counseling appointments. Both issues have been chief concerns among administrators and students alike. On average, small schools have one counselor per 1,000 students. While Ivies are hiring more mental health staff, diversity varies by campus. Cornell, Dartmouth, Yale, and Brown’s counseling staff were remarkably homogeneous. This is concerning because Black and Latinx populations are more likely to be depressed than white people. For years, western psychologists overlooked depressive symptoms in Chinese populations because they lacked cross-cultural competency. Having diverse, culturally aware therapists to aid stressed students of color is a matter of life and death.

When students receive care they are more successful. However, it’s very common for students with longstanding trauma to exhaust campus therapy visits. Despite a 30% increase in college counseling center visits nationwide, Harvard, Dartmouth, Princeton, Yale, Brown, Cornell, Columbia, and the University of Pennsylvania adhere to short-term models of care. If mental health support is proven to help students and they're willing to seek it out, why don’t Ivy League schools offer long-term campus care?

A Columbia administrator said visit limits are a myth. Counseling and Psychological Services have 35,000 visits per year. Columbia Health anticipates that a quarter of students across its schools will utilize CPS at some point. Their current staff of 50 clinicians isn’t large enough to offer unlimited visits for all students and see new patients. To avoid excessive wait times, people need to be discharged at some point. Hence, Columbia and its peers adhere to a short-term care model.

Due to their inability to offer long-term care, Columbia and its peer institutions have built a robust network of referrals. People with Columbia’s insurance pay no more than $20 for off campus therapy. Given the cost and time of travel, campus care will always be the most accessible option for busy students. Once care is no longer affordable or convenient, people can fall through the cracks.

After running out of CAMHS visits, Harvard told a student they would find Black therapists and reach out to them on his behalf. Harvard never contacted any counselors. Instead, they sent the student a list of predominantly white clinicians.

Courtesy of Savannah Lewis

A student at Brown who asked to be referred to as Silver, identifies as psychiatrically disabled. They live with autism, anxiety, depression, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD), and dissociative identity disorder (DID). Their mental illnesses have framed their college experience.

“My entire schedule has to be flexible in case something happens with my mental health,” said Silver.

For Silver, crisis is normal. Being in close proximity to other students 24/7 can make college overstimulating for anyone, but especially for Silver. Autism predisposes them to sensory overload. Brown’s party culture was too overwhelming, so finding friends took time. Isolation from the social scene contributed to their depression. Silver has to constantly manage their C-PTSD triggers. Their personality switches aren’t emergencies, but things can get complicated. Silver’s different personalities have unique needs and separate memories.

Despite all of these obstacles, Silver only disclosed their depression to Brown’s Office of Disability Services. They want to keep their more serious disabilities off the books. Organ donors can legally discriminate against people with psychotic disorders. People with DID who receive personality integration therapy are more likely to get organ transplants than those who don’t integrate their personalities.

“If I can do something to get around that, I will always take that route,” said Silver, “it’s physically safer for me to do so.”

Even if they chose to reveal their other conditions to Brown, they couldn’t help. Most students can get a few campus sessions in before being referred off campus. But people like Silver are immediately turned away.

“Once you hit that moderately to severe mentally ill end,” said Silver, “they don’t have any resources for you.”

All of Brown’s counselors are social workers and general therapists. None of them can remedy severe psychological disorders. It’s possible to specialize in treating a few disorders and still work as a general therapist. Silver says there’s no excuse for Brown’s failure to hire people who can serve those with severe mental health conditions.

“Typically I take a slightly longer route in hopes of catching a bus,” said Silver.

Silver spends thirty minutes walking to and from therapy every Wednesday. It’s usually cold outside. The busses in Providence, Rhode Island are often unreliable. Brown’s OnCall and Disability Shuttles assist with food insecurity and accessibility issues. Silver wishes they had a similar service to accommodate the people who are referred off campus for therapy.

Brown is currently revamping its mental health system. As of 2017, Brown students are eligible for unlimited campus therapy visits. Silver thinks the school could better advertise its long-term services. For years, students have rallied for a Disability Culture Center but the negotiations are “caught in red tape.” Silver wishes Brown would embrace disabled students in their words and their policies.

When it comes to mental health crisis support, Silver says Brown has a long way to go. So do its Ivy peers.

“There is no structure within the larger structure of Brown that holds space for mental health crisis that’s not transportation,” said Silver.

Often, mentally ill students call Emergency Medical Services (EMS) to help calm down. Silver said these calls often end with a student being transported and involuntarily hospitalized. There is no education for the general population on handling psychotic episodes.

“It feels like a black and white situation right now,” said Silver, “you either go to your peers or you call EMS and get involuntarily hospitalized.”

If forced to choose between the two, Silver would rather have a peer support model. They say involuntary hospitalization isn’t treatment, it’s containment until suicidal urges go away. Usually it leaves students feeling more unwell. But even student led care systems have drawbacks.

Resident advisors (RA) like Tomás Reuning, Cornell ‘21, play a crucial role in students’ mental welfare. They are, in essence, a university’s first responders. Because they live among students, RAs are often their first point of contact during crises. Reuning loves his job but says $500 a semester isn’t enough for around-the-clock emotional labor.

“The hours are insane,” said Reuning, “I had an on-call issue where I was woken up at 3 o’clock in the morning to deal with it and I was up until 8:30 in the morning.

It’s a huge sacrifice for someone with a history of anxiety attacks. Reuning has also lived with depressive symptoms since age 12. He relies on an emotional support animal. Being trans, he has his own grievances with Cornell. Wearing a binder helps with stress and anxiety. He can’t leave home without it. Last semester, Reuning hurt his back. He couldn’t put on his binder, so he had to miss class. His professor required a doctor’s note but Cornell Health no longer gives class passes. They believe professors should trust students. Reuning also mentioned that requiring doctors notes can alienate poor students. Cornell’s institutional contradictions are the product of its decentralized approach to care. And it makes life harder for students like Reuning.

Despite these obstacles, he keeps his draining job. It’s the easiest way to pay Cornell’s student contribution. He can also avoid the school’s tricky housing lottery. Compromising emotional boundaries to be a key player in Cornell’s peer support system is Reuning’s only option.

Peer support models usually include mandatory student reporters. Reuning hates it, mostly because of Cornell’s Title IX Office. They’re supposed to stop discrimination, but Reuning says they have a record of disregarding students’ agency. Reuning only reports things that are expressed to him in his capacity as an RA. Sometimes being deputized by Cornell puts him in a, “really weird position,” with his residents because they’re also his friends. Mandatory reporters are quite knowledgeable about student resources. However, students may not want to be vulnerable with people who could easily report them.

When mandatory reporters are not properly trained, they can make mental health crises worse. In many cases “worse,” means involuntary hospitalization. University of Pennsylvania student, Amina Jones, was involuntarily hospitalized by a counselor at Penn. Her real name has been changed for privacy reasons.

At age 14, Jones told her mother she had bipolar disorder. Her mother didn’t believe her, so she first received care during her freshman year at UPenn. After a year of counseling, Jones realized she needed a psychiatrist. She fell into a deep depression and took a medical leave in the spring of her sophomore year. During that time, she began seeing a psychiatrist who didn’t specialize in bipolar disorder. She prescribed Geodon and Prozac, two medications that do not interact well. Jones said it made her face twitch.

She returned to UPenn in fall 2018, focused and ready to work. While sipping coffee to study, Jones suddenly felt an intense suicidal drive. She sat in her lecture shaking and sweating. To cope, she called her mother, took a nap, and went back to studying.

Three weeks later she asked her therapist to document the episode. Instead, security guards transported her to a hospital in a wheelchair. She wasn’t allowed to be by herself, not even to use the bathroom. After she was committed, they presented a form where she could “voluntarily” consent. Feeling like she had no choice, Jones signed the form.

She was placed in a room with fluorescent lights, a large barred window, and a red line on the floor. Jones was exhausted. So, she went to sleep. Hospital employees woke her up at 5 a.m. the next day and asked her a series of questions. As they were explaining that she’d have to go to court to be released, Jones reminded them that she was there “voluntarily.” Then, they read her patients’ rights. Shortly thereafter another doctor determined she was okay to be discharged.

The 13 hour ordeal cost Jones $4,000. It will be on her record forever. Her French professor gave her a zero for missing class. She is considering taking legal action.

How do students cope?

Each student mentioned in this story noted stimulant abuse on their campuses. This came as no surprise to Dr. Carleah East. She’s a psychology professor and Mental Health Lead at St. Petersburg College.

“You need to be worried about Xanax, Zoloft, Concerta, Adderall, and Ritalin,” said East. “Those are the ones they crush up and snort.”

During her 18 years as a psychotherapist, Dr. East noticed that people create hyperactive behaviors and brains. She says society’s “fast-food mentality” compels students to use study drugs that aren’t prescribed to them. It’s a quick fix for workload problems, and a recipe for long-term health issues.

“I say, ‘OK, well, I'm just gonna take this [drug] to study.’ I get off of it. Guess what? My brain is not producing as much melatonin as it used to because the chemistry of the brain has changed. So now I can't sleep,” said Dr. East. “Now I have to take something to help me sleep.”

She said that’s why students use alcohol and weed in excess to relax. The brain’s chemistry has changed, and its tolerance increases. People have to take more medicine to get the same effect. That can lead to a host of problems.

“Heart attack, stroke, panic attacks, dizzy spells, head migraine headaches, tourette-like ticks like rolling of the neck,” said Dr. East, “Those are things that also come out of being overmedicated or taking medications that are not prescribed to you.”

Liver dysfunction and kidney failure are among the worst health risks. Still, extreme pressure and wealth makes study drugs fairly accessible on Ivy League campuses. Sarah, a junior at Columbia, has been using study drugs since age 16. Her real name has been omitted for her protection.

In high school, ecstasy was Sarah’s study drug of choice. It was a crucial element of her mock trial practice ritual. A few lines before a mock trial tournament gave her team the fire they needed to win. It was nothing to Sarah. She had already tried weed, acid, coke, and Xanax. The most her mom did was confiscate her rolled up two dollar bill. It didn’t matter, she’d already been admitted into Columbia. The stakes were low, so she got sloppy. Sarah maintains she was never addicted, just bored. There was nothing else to do in Louisiana.

New York was exciting. Sarah didn’t need ecstasy as a freshman. Although her roommate spent eight hours a day in Butler “just to say she did it,” Sarah hadn’t succumbed to Columbia’s stress culture. Instead, she capitalized on it. While most Columbia students are initially hesitant to take study drugs, Sarah says desperation compels them to try.

“This guy had to get very desperate for him to take the ecstasy from me,” Sarah said.

Sarah didn’t hit rock bottom until her sophomore fall. She was taking 18 credits. Smoking weed helped her manage her anxiety. ‘Twas the night before finals when she downed her boyfriend’s 15 mg immediate-release adderall with a cup of coffee.

“I know if I do a certain amount of stimulants,” Sarah said, “I'll work through the night, take the tests, and be fine.”

When Sarah realized how lucrative Adderall sales could be, she bought 30 pills. She paid two dollars per capsule. Upon returning to campus, she began charging seven dollars per 15 mg immediate-release tablet. Soon, Sarah got a prescription for 10 mg extended-release Adderall to help with her fatigue. She dosed up every other day to stay a week ahead in class and still have time for guilt-free fun. Every pill she didn’t take got sold. By the end of the semester she was out of inventory. Midterm and finals seasons were quite profitable.

“People would take huge numbers off of me at a time.

It was never one or two, it was like ten.”

- Sarah

She says one customer would stash pills and give them to his friends. Most of her clientele were men. Women were more apprehensive about buying. She served people of all races and majors who were mainly juniors and seniors. So far, nobody has overdosed.

Sarah admits to doing more drugs than the average Columbia student. She believes they should be legalized. Columbia Health flyers discourage study-drug usage by indicating over 90% of students don’t use them. Sarah doesn’t think the posters are effective or accurate.

“They don’t work, first of all,” said Sarah. “Yes, prevent people from getting addicted [to drugs], which means reducing the stress culture.”

Basically, tackling stress culture is the best way to stop people from becoming dependent on drugs. Everything came to a head during her sophomore spring. Sarah had a psychotic break.

“I had started cleaning my room and all of a sudden I was like ‘I’m going to get rid of everything that I don’t need,’” said Sarah. “Within 30 minutes my whole room was in two huge garbage bags.”

She was hospitalized for five days. Sarah was diagnosed with depersonalization derealization disorder. Sarah believes she had the disorder in high school, but it became apparent at Columbia. It made her blank out and stare at walls for hours. She dissociated at random – even in class. Sarah says she’s in great health, but has trouble sleeping.

Sarah’s story exemplifies many of the phenomenons Dr. East described. At Columbia, she began using someone else’s Adderall prescription to keep up with academics. Due to her prolonged drug usage, her body built a tolerance to stimulants. Hence, she had to pair a 15 mg Adderall with coffee to feel its effects. She became dependent and needed her own prescription. Her stimulant abuse likely triggered an underlying disorder, which caused her to be hospitalized. Sarah finds it hard to sleep and smokes weed to relax.

Many students cope by venting online.

Several of Michael Clarke’s tweets about Harvard have gone viral. Clarke’s real name has been changed, per his request.

“I think Twitter is a very good way to engage people with similar experiences to form some sort of coalition or some solidarity around what's going on to us at these schools and elsewhere,” said Clarke.

The tweet was Clarke’s last resort. The majority of his recent tweets praised Harvard. He could never hate his dream school. At 15-years-old Clarke left his home country of Jamaica to maximize his chances of attending Harvard. Once he got in, he became a teacher’s assistant to give students the support he wished he’d had. Clarke says there were plenty of times students and teachers made him feel unwelcome. One particularly sour interaction with a professor inspired his first visit to Harvard’s Counseling and Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

“I emailed my professor directly and he responded to my two paragraph long e-mail like ‘no.’” said Clarke. “And yeah, I fully broke down in Harvard Yard. I was walking to a meeting and I had to cancel my day.”

He eventually received an extension, but only because an administrator asked on his behalf. When a students’ needs are dismissed, it can destabilize them.

Universities: Need help? Use our mental health services!

— Gabi Drolet (@gabrielledrolet) January 27, 2020

The services:

-A golden retriever comes to the library once a week

-There's one therapist on the campus of 40,000 students

-There are bathroom stalls you can cry in for free!

my mental illness don’t agree wit the strict attendance policy some of these profs got in place ..

— sabbiг (@sabbyinthelab) March 3, 2020

I’ve accepted that I’m not going to turn in my work on time, and that’s ok. I am not jeopardizing my health anymore for a school that literally does not give a fuck about me. My work will get done when it gets done. Good night y’all

— Josué (@burntchikinnugz) March 2, 2020

Students cope through innovation.

Like many students, Clarke’s tears were an emotional response to distress. Mahzabin Hasnath, Columbia ‘19, cried plenty of times at home, but never on campus. At least, not for a while. She is the oldest child to Bengali immigrants; born and raised in the Bronx. As a teenager, she woke herself up for school at 5 a.m., rode the bus alone, worked through her lunch period, and did her homework in the evening. She was accustomed to being self-sufficient, not vulnerable.

Coming to Columbia after graduating from the Bronx High School of Science meant going from “one stressful environment to another.” She often felt “small” in large introductory computer science classes. Knowing that many of her peers were far more experienced programmers was overwhelming. Next to none of her professors were women, much less women of color. They were mostly white men. Hasnath says the lack of representation and vastness of her classes made her feel like her problems didn’t matter. She preferred to cry at home until a difficult programming assignment brought her to tears at Barnard. She says the moment was “freeing.”

“It’s okay to need help,” said Hasnath, “I want someone to hold my hand and I will cry because I'm human and we have emotions. I won’t let anybody tell me otherwise.”

After that, being vulnerable with her professors became easier. Hasnath says she was most comfortable being open with her femme professors in humanities departments. For her final web design class, she created Crying @ CU. She described the website as a geospatial storytelling platform for life’s emotional moments. It was inspired by Crying In Public. Her platform allows people to anonymously tag places where they’ve cried at Columbia. Over 30,000 people have visited Hasnath’s site. She made the platform anonymous to stress the importance of human connection. By using maps, Crying @ CU encourages users to think about themselves in relation to others. It’s also useful to understand how and where people process emotions on campus. She admits the entire premise of her platform is “so millennial.”

“Our parents’ generation, they would never send out a tweet like, ‘Hahaha I’m gonna kill myself,’ said Hasnath. “It’s so nonchalant. But are we desensitized to it? Are we so used to going through pain that it becomes a funny tweet or ‘How can I monetize this for internet clout?’ How millennials process grief is really interesting to me.”

If she could change anything, Hasnath would increase empathy between students and professors. Universities create cold environments when they direct students to a policy rather than offering help and compassion. Hasnath says it makes people feel less inclined to be open.

“That’s when you have students suffering academically and emotionally,” she said.

As a freshman, Sanat Mohapatra, Dartmouth ‘20, was suffering academically and emotionally. He was still transitioning to Dartmouth. He failed a test and felt like he was drowning. Realizing that his classmate, Adam Wright, was absent because Wright had committed suicide didn’t help either. A bad initial consultation with Dartmouth’s counseling center compelled Mohapatra to find new ways to cope. This often involved responding to mental health related posts on Yik Yak, an anonymous messaging app.

That semester Dartmouth’s Yik Yak shut down due to harassment issues. Nevertheless, Mohapatra saw an opportunity to help his peers. He spent the next three years developing Unmasked. It’s a moderated app where anyone with a Dartmouth email can vent about mental health challenges and discover University resources. So far, it’s been downloaded 900 times. That’s a lot for a relatively small school like Dartmouth. There are between 20 to 25 posts in a single day.

Hundreds of user confessions are inspired by a simple question: “Hi, how are you really feeling today?” Mohapatra says his app is accessible because “kids nowadays prefer the virtual.”

Mohapatra’s Unmasked App

“When you're struggling you’re having thoughts about the world that don’t reflect reality,” says Mohapatra. “It’s anxious thoughts like ‘everyone hates me, no one cares about me.’ This is a way to express those thoughts and then realize there are a bunch of people who care about you.”

Dartmouth suggested that Unmasked shut down before it ever launched. They were concerned about liability issues. Furthermore, they didn’t see the university’s role in harming students' mental health. Mohapatra’s mantra is different.

“There are many people that are struggling right now that aren’t being serviced by the existing mental health resources,” he said. “Dartmouth doesn’t see it as an imminent, pressing, urgent problem.”

Mohapatra said Dartmouth usually responds to student mental health crisis by listing existing services. Group therapy, emotional support animals, and peer support are great, but they don't help everyone. Mohapatra refused to shut down his platform because “people needed the app.” He has the proper insurance, professional counselor support, strict community guidelines, and a skilled moderation team. Unmasked only turns over data if students post imminent threats to themselves or others. Dartmouth believes in Mohapatra’s vision, but they can’t publicly endorse the app.

“There are a lot of posts about suicide,” said Mohapatra. “My logic is, if the app didn’t exist it’s not like those kids go away. They just don’t have anyone to talk to.”

In accordance with expert opinion, Mohapatra believes suicide shoule be discussed like any other health condition. There’s no research that says talking about suicide increases ideation. So, Unmasked builds community around tough topics. He hopes to bring Unmasked to other campuses.

By analyzing Ivy League students, Surviving Ivy discussed ways that institutions of higher learning mistreat, neglect, and discriminate against students experiencing mental illness. When that happens, parents like Angie Wallace and countless others have to bury their children. Universities are often people’s first homes away from home. They have a unique relationship with their students and a duty to provide care.

Some students noted that lack of access to sunlight and green space makes them depressed. This is likely because Ivies are situated in the Northeastern United States. Most of the school year occurs during daylight savings time, in the cold. Dorms may not receive optimal levels of sunlight. Still, there aren’t enough studies to determine whether the spatial geography of college campuses affects student mental health.

Many of the people in this story have been sexually assaulted. It’s unclear whether students’ faith in college support for survivors is related to general levels of student stress. The data doesn’t exist. There are numerous studies about campus suicide, but few focus on elite schools.

Most of the students mentioned were Black, brown, or identified as a person of color. In terms of economics, the overwhelming majority came from poor or working class families. Statistically speaking, they’re already predisposed to psychiatric symptoms. When these students seek care at school, it’s usually because they can’t get it at home. Answering their pleas for help with pressure to leave is classist.

I asked a Harvard administrator about its willingness to evict housing insecure students on March 7, 2020. By March 10th, they moved to forcibly evacuate undergrads during a health pandemic with less than a week’s notice. They did not cancel class. Dartmouth, Brown, Cornell, and the University of Pennsylvania also kicked their students out during their time of need. Actions like these explain why vulnerable students are often the most stressed.

Students with mental illnesses and disabilities needed virtual class before Coronavirus. It’s unfair to expect people like Silver to miss no more than two classes in a fifteen week semester. Universities transitioned to virtual classes within a week. They had the infrastructure to become more accessible. Yet, virtual classes are not offered as a disability accommodation.

In light of Columbia’s suicides, I expected a host of wrongful death lawsuits. I found none. It’s unclear if people are too bereaved or too poor to sue, or if Columbia settled out of court. Current legal precedent doesn’t require much. If a college provides some level of suicide prevention and mental health services, it’s hard to successfully sue them for wrongful death. Cornell, Columbia, Harvard, and Yale have worked with the JED Foundation to stop suicide. JED’s program is effective, but it ends in four years. Theoretically, a school could “finish” JED’s plan, fail to maintain initiatives, and still be a JED Certified Campus. This can happen if campus priorities change with leadership. JED s long term institutional investments in mental healthcare, but they can’t guarantee it.

Courts do not require colleges to provide long-term psychiatric care. If they did, Ivy League schools have the capital to make it happen. Adjudication often means compliance, and that’s exactly how Harvard attempted to get Luke Tang’s case thrown out. Harvard knew that Tang had attempted during his freshman year. A year later, Tang committed suicide in his dorm. His lawyers allege that Harvard’s “negligence and carelessness” resulted in Tang’s death. Harvard argued that they complied with the duty of care established in an MIT case. Middlesex County Superior Court denied Harvard’s request to dismiss Tang’s lawsuit. Tang’s case presents an opportunity for courts to reevaluate institutional culpability for student suicide.

If more people sue colleges for wrongful death, insurance companies will take note. Widespread sexual assault inspired insurance companies to hike insurance premiums for some K-12 schools. Colleges have similar insurance policies. Schools could be incentivized to take suicide more seriously if companies raised their insurance premiums.

Surviving

Casey Thomas' story demonstrates that saving lives means changing how society treats mental illness. Their name and other details have been omitted to protect their privacy. Thomas survived a suicide attempt at Columbia.

Thomas says they started college, “a day late, and a dollar short.” They were outed by a Columbia student during a campus recruiting trip. It hurt because they weren’t secure in their sexual identity at the time. Thomas' situation worsened when a former friend began harassing them. Their friend will be referred to as Brian. At first, they were close.

“I wasn't really doing that well, so it felt nice,” said Thomas. “I was under his wing. I was a very strong bird, but I needed a little bit of time to heal because I just got off on the wrong foot.”

Brian developed unreciprocated feelings for Thomas. When he noticed them withdraw, he began stalking them. Brian also spread a rumor that Thomas had raped somebody. Thomas and the alleged victim maintain that it never happened. But Brian was an upperclassmen, and people trusted him. Because of the rumor, Thomas was never able to get respect or recognition in the club. Brian turned everyone against Thomas.

“I think he saw vulnerability in me and he took advantage of it when I wasn’t capable of giving him what he wanted,” said Thomas.

The situation left Thomas in a bad place. They developed a tremor from being so anxious. As they rehashed the story, I saw them shake. It was hard for Thomas to find community while they were being attacked. I asked them why they never blocked Brian.

“I was scared of people hating me,” said Thomas. “I didn't want to give people more of a reason to hate me. I thought they already thought I raped a girl, which didn't happen. But no one believed me saying it.

Brian’s rumor triggered their own memories of sexual assault. Thomas informed a university staff member, but he never reported anything. With a 17 credit course load, Thomas didn’t have time to process all that had happened. They decided to shoulder everything until they had time to seek help. After pulling out a 3.6GPA, Thomas began searching for a psychiatrist.

Deep down, Thomas knew help was long overdue. They first experienced suicidal thoughts at age 11. Thomas recalled chilling exchange with their mother.

“I don’t know what it means to know you can have everything in the world, but also know you deserve none of it, and you actually have nothing.

I was 11 or 12 years old.”

“I looked at my mom just so sad. I was like, ‘I don't know what it means to know you can have everything in the world, but also know you deserve none of it,” said Thomas, “and you actually have nothing. I was 11 or 12 years old.”

At 13, they told their father they wanted to die. In response, he said that Thomas would learn to become “comfortable” with it. Thomas’ family was well off. They requested therapy but never went. Thomas parents said they “forgot” to seek mental health support for their child. So long as Thomas excelled in her school and activities, nobody was concerned.

In December 2019, Thomas’ sibling introduced them to a psychiatrist. He was known for not over-medicating clients. This was extremely important because the class of drugs used to treat depression, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), are tricky. Everyone’s body chemistry is different. SSRIs can have debilitating side effects such as insomnia, weight changes, and vomiting. Finding the appropriate prescription can take months. Thomas trusted their doctor. When he prescribed Xanax and the maximum dosage for two SSRIs, they complied.

“I was on a lot of medication,” said Thomas. “I wasn't sleeping, I wasn't eating, I was manic.”

The doctor changed their medications. By February, they were taking a host of sedatives for anxiety, a “happy pill” for depression, Adderall, and Trazodone. Once Adderall started giving them heart palpitations, the doctor prescribed Vyvanse. They were a “walking pill.” Thomas took stimulants and SSRIs in the morning and sedatives and more SSRIs at night. Sometimes, they felt okay. Xanax transformed them into the person they wanted to be. In fleeting moments, Thomas didn’t assume that people viewed them through Brian’s rumors. Carrying the heavy memories of their assault was bearable.

Thomas was prescribed at least six medications in less than 3 months.

Most of the time, Thomas said the drugs made them dizzy and sleepy. They stopped taking Mirtazapine after they gained thirty pounds. It provoked an old eating disorder. The combination of drugs gave them painful headaches and regular stomach pains. Thomas couldn’t sit through class. Missing school made them so anxious they developed a nervous tick: scratch their head until it bled. Continuously explaining absences to professors was tiring. Thomas was unable to perform well academically. When they weren’t barred out, they were consumed by feelings of inadequacy, shame, and guilt.

Towards the end of the month, Brian broke Thomas’ nose. It was an accident. Reluctantly, they went to the hospital. The sterile smell, bright white lights, and presence of death made Thomas anxious. It didn’t help that their family had previously threatened to hospitalize them.

“It seems like you go to get help when you're at risk of getting other people hurt,” said Thomas. “It's not because you actually need help. So, I felt like I was forced to be there rather than going there for myself.” They had a nervous breakdown.

Then Brian called.

“He was like, ‘I will literally fucking kill myself if you if you don't love me back,’” said Thomas. “All this crazy shit. I'm like, ‘What the fuck are you talking about? He's like, ‘These kids, they don't love you.’”

Brian had sent Thomas hundreds of text messages like that. Their system was flooded with antibiotics, SSRIs, and Xanax. Coming off of a mental breakdown made everything worse. Brian’s call threw them over the edge. His gaslighting and manipulation distorted Thomas’ reality. Gradually they descended into a nightmare where Brian and the club called them a drug addicted rapist. They were a complete failure, and had the grades to prove it. Being estranged from family made them feel unloved. Now more than ever, Thomas felt like a burden to society. They were “drowning.”

Thomas knocked on a friend’s door with dangerous levels of meds in their system. They asked a friend why they deserved to live. Fortunately, their friend knew how to handle overdoses.

Thomas survived, but they were very sick.

Between March and April, Thomas caught two strains of the flu, sinusitis, strep throat, and a fungal infection. Their immune system was completely compromised. While Thomas was fighting for their life, they said Columbia was more concerned about academics. Their professors were upset that an administrator that wasn’t Thomas’ advisor had to step in. Thomas felt like their advisor could care less if they were healthy or not, so long as there wasn’t another campus suicide. Rather than asking what Thomas needed, they wanted to know if and when they’d finish their work. During that time Thomas exchanged over 55 emails with professors and Columbia staff. All correspondence was about work. Even if people did ask how Thomas was feeling, they couldn’t be honest.

“If I was honest, I would get kicked out,” said Thomas. “So, I felt like I was lying through my teeth doing assignments that were overdue.”

The stakes were high. They had no choice but to do well on a “million” papers and makeup assignments. Taking another extension wasn’t an option. If Thomas didn’t rise to the occasion, they would be forced to reapply to Columbia. They would send Thomas home to the same father who said girls need boyfriends, not medication. Doing “triple” the work with only a quarter of their strength was the best option Columbia offered. Somehow, Thomas pulled through. They wished the school had taken a different approach. They would’ve liked to focus on attending the remaining classes and worry about work over the summer.

In hindsight, Thomas admits they should’ve taken time off. But they didn’t want to disappoint their family. Being in the club wasn’t healthy, but depression made them cling to what they knew. Thomas says they spent so much energy apologizing to family, professors, administrators, and friends for being mentally ill, they forgot they had done nothing wrong. Now, Thomas is in a much better place. They weaned themselves off the medication and got a new doctor. They now take less medication half as often. Thomas says their progress isn’t linear. Tessa Majors’ passing away, made Thomas reckon with their mortality. They couldn’t stop thinking about almost being “the standard suicide email that every kid archives.”

“I realized kids like me are looking at the same emails substituting their names and grad year,” said Thomas. “Maybe their major if Columbia was decent enough to look into it.”

Surviving Columbia is still an uphill battle. Thomas still scratches their head as a nervous tick, but not to the point of bleeding. In those moments they put down the books and try to feel whole. In the future, Thomas hopes to pursue a career related to mental health education for doctors and children.